October 30, 2018

From Nonprofit Quarterly: Growing Maine’s Rural Economy--Understanding the Coastal Enterprises Model

The following article appeared in Nonprofit Quarterly on October 16, 2018.

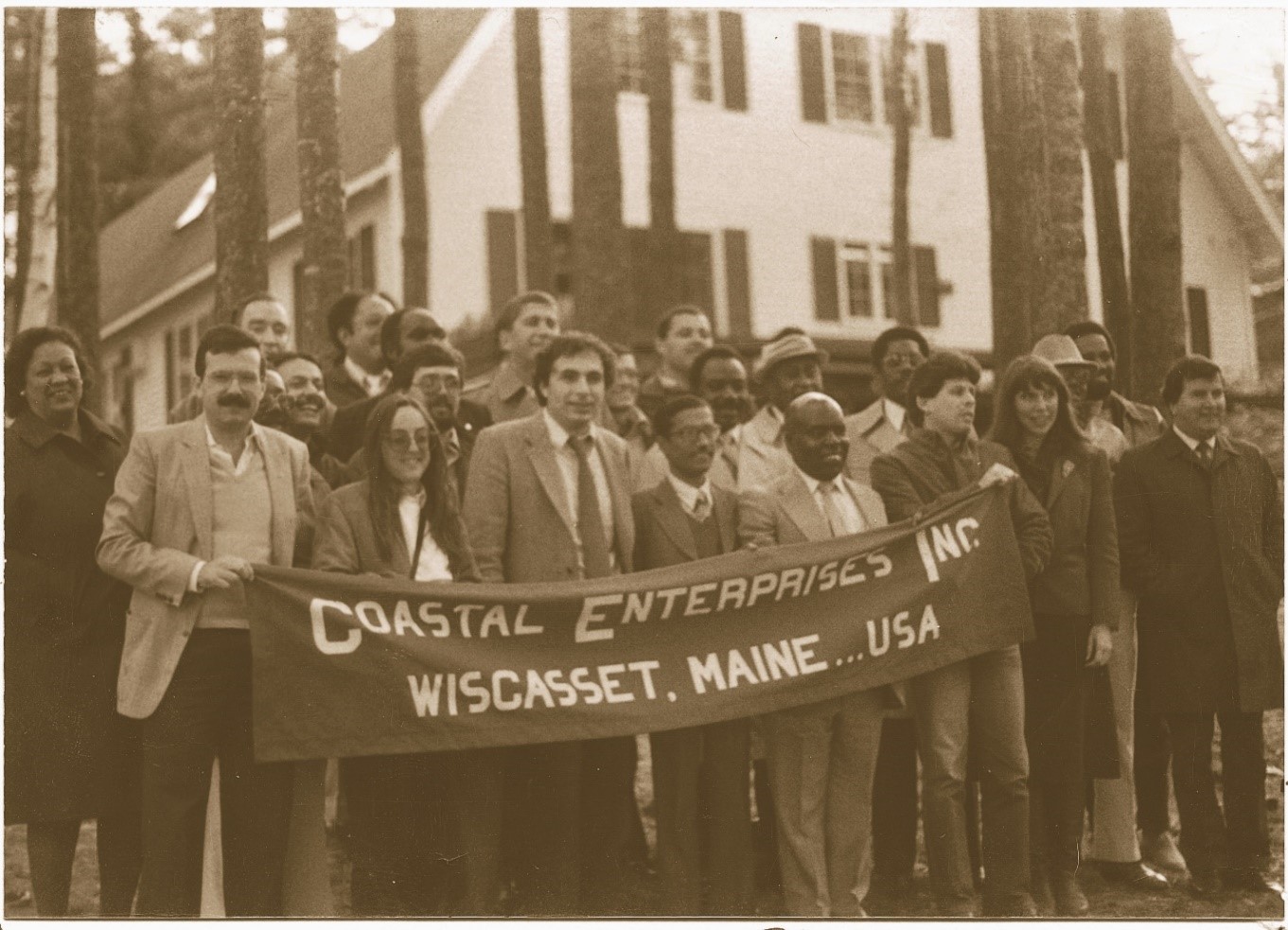

Founded by a seminary school graduate in 1977, Coastal Enterprises, Inc. (CEI) has become nationally known as a leader in community economic development and community finance. The story of its work over 41 years in Maine may hold lessons for community development in rural communities far beyond the state’s borders.

Maine’s 3,500 miles of coastline, with craggy peninsulas, islands and diverse geography, is considered by many to be its most valuable, unique natural resource. A visitor traversing the state via Coastal Route 1 might describe all the communities along the Gulf of Maine and its islands as quaint. But that belies the diversity of the communities, culturally and economically. Maine’s fishing and marine heritage is evident at nearly every turn.

Coastal Enterprises, Inc. (CEI) was incorporated in 1977 along this route in Bath, Maine, a small city that today has about 8,300 residents. Then, a startup nonprofit with no money in the bank, its founders had an audacious vision to expand economic opportunity for people living along the mid-coast of Maine. Its first project was to create a fisherman’s co-op in Boothbay Harbor and make a startup loan. This sparked a model of advancing economic justice that CEI has honed over the past 40-plus years in its home state and, through its subsidiaries, in rural regions across the US.

One of the nation’s first community development financial institutions (CDFIs), CEI has financed more than 2,700 businesses, providing $1.3 billion of capital, with another $2.8 billion leveraged on top of that. This combination of lending and investment activity has helped create and sustain close to 40,000 jobs and create and preserve more than 2,000 affordable housing units. Now headquartered in Brunswick, Maine, CEI employs 81 people.

CEI’s 41-year history holds lessons for community development in rural communities far beyond Maine’s borders. To get a better picture of the model, let’s take a closer look at an industry in which CEI has played a critical catalytic role—namely, Maine’s fisheries.

Like many rural, resource-based industries, fishing is prone to boom-and-bust cycles. On paper, Maine’s fishing industry may look like big business, with over $560 million in landings—that is, fish hauled in from the sea—recorded last year. In reality, it is mostly made up of a string of small businesses, often family-owned and operated. Over the years, this ecosystem of small businesses has been buffeted by global factors mostly out of its control—from climate change to overfishing to the vagaries of consumer demand.

While Maine’s landings of seafood are the third-highest in the United States, more than 90 percent of the seafood consumed in the nation is imported. Maine’s historic commercial fisheries focused on groundfish, shrimp, lobster, and sea urchins. But many of these species have disappeared. Lobster catches are currently holding Maine’s industry together.

That may be about to change. The Gulf of Maine Research Institute recently forecast that fast-warming waters could cut the lobster population in the Gulf some 62 percent by 2050. Maine’s waters have already warmed faster than 99 percent of the world’s oceans, as natural variations in the Gulf Stream and the Atlantic Ocean exacerbate warming trends.

Adjusting to change is anything but automatic. Many small, incremental shifts gradually move a community from one economic environment to another—a slow, grassroots evolution. The resilience of this industry is due in large part to the fishermen themselves. The field remains overwhelmingly male-dominated, although women’s presence in the industry is growing: close to one-in-ten fishery license holders is female. We use the term “fishermen” (or “lobstermen”—a dominant fishing industry in Maine)—because the term is used in practice by both male and female “fishermen.” Maine’s fishermen are valued for their commitment to what they know how to do best, a way of life, and an obligation to steward the environment that provides a livelihood.

Like other natural resource industries, the health of a fisheries economy is interdependent and relies on more than a biological ecosystem to survive and thrive; it depends on a community ecosystem too.

An Ecosystem Approach to Economic Development

1. Community Building

A central element of this ecosystem approach involves listening and outreach. Throughout coastal Maine, the work to transition the fisheries economy is dependent on innumerable encounters—some planned, others spontaneous.

Community organizing at its most granular level often starts with just a handful of people listening, then convening, then developing resources and information. CEI uses its mission lens to assure basic rights and tenets of social equity through policy and practice. Follow-through over the course of years builds trust and encourages leaps of faith into the future. It’s this aggregation of social capital that is vital to economic growth in rural places like Maine.

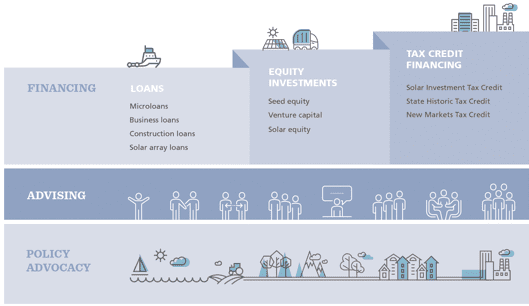

2. Financing

Access to capital with reasonable terms and cost is a critical factor in supporting a transitioning economy. This included making loans for groundfish boats back when that was still a viable industry. As market conditions shifted, so did financial support. CEI began making more loans for lobster boats and—through its subsidiary CEI Ventures—has found opportunities to inject equity into innovative growth businesses.

CEI has been able to tide over many small operators with financing that banks or other lenders are not willing to provide. Deep vertical industry knowledge is a key element that allows for accurately gauging the risk involved, which makes it possible to support small entrepreneurs.

Starting in 1994, CEI’s Fisheries Project began supporting the state’s fisheries adjustment strategy to support Maine’s commercial fishing fleet and exclude foreign vessels from fishing in Maine waters. Revolving loan funds from the state were matched by CEI’s funds and foundation grants to offer fixed-rate financing from $5,000 to $150,000. Venture capital and other types of financing were added to the mix to help seafaring businesses achieve greater scale. These loans and equity infusions have helped finance harvesters, processors, shoreside suppliers, new marine-related enterprises, and diversification projects for displaced fishermen.

3. Technical Assistance

Resilience requires more than money. Small business owners benefit from technical assistance as they look to the future and recognize a need to diversify their catch. CEI is host to Small Business Development Centers up and down the coast, available to help entrepreneurs master cash flows, marketing, and food safety requirements as they start and scale their businesses.

With the strong belief that diversification protects Maine’s fisheries economy from climate change impact, CEI was at the table for the creation of the Maine Aquaculture Association, helping to literally write the book on how to farm crops like mussels, oysters, sea vegetables (kelp and seaweed), and most recently scallops.

Workforce development is a core service too. CEI helped establish the “Aquaculture in Shared Waters” program to prepare today’s commercial fishermen to succeed in an aquaculture career and to start a sustainable shellfish (e.g., mussel or oyster farms) or sea vegetable business. The 10-week program combines classroom training with hands-on workshops and field trips to introduce participants to all aspects of an aquaculture business, including the mindset shift from hunter/gatherer to farmer. The program is an ongoing collaborative venture involving CEI, the Maine Aquaculture Association, the Maine Aquaculture Innovation Center and staff from the Maine Sea Grant program.

4. Policy

From the beginning CEI has functioned as a thought leader and advocate for policies to support fisheries. In the late 1970’s CEI’s young staff recognized how federal fisheries laws created new commercial opportunities for smaller boats and brought knowledge and loans to Maine’s fishermen.

CEI has had a hand in creating policy over the years too. A prime example is the Working Waterfront Access Protection Program, designed to maintain the critical land/sea marketplace in the state.

When landings come into a wharf, fishermen need to have infrastructure to welcome the catch. A wharf is a micro community in itself, and waterfront accessibility is critical. It’s where the fishermen park and support other small business when they fuel up, buy bait, land and store their catch, conduct transactions, and load product for ground transport. Commercial fishing success relies on waterfront accessibility along the entire coast, an increasing challenge as coastal property is bought by private developers and second homeowners.

The genesis of the waterfront program was an outcome of countless conversations over the years. Those talks eventually became more formal when, in 2002, CEI researched the problems regarding access to and maintenance of fishery properties. Recurring complaints they heard from borrowers and neighbors included factors such as rising property taxes and ongoing investment needs.

Taking a policy approach, a coalition including CEI advocated for catalytic capital in the form of Maine state bond funds. Eventually, the legislature created two programs that protected 25 commercial fishing waterfront properties in diverse locations along the Coast, and 100-plus additional properties were registered for a tax break to maintain access for fishing.

From this work and the relationships it forged, the Maine Working Waterfront Coalitionemerged. Building on its study of 25 coastal towns in 2002, CEI reached out to other groups like the Maine Lobstermen’s Association, Maine Aquaculture Association, Maine Marine Trades Association, and Island Institute to pull together a core group of entities and individuals. The coalition convened monthly in the state capital for the sole purpose of assuring waterfront access.

5. Co-development of New Products and Industries

Entrepreneurs rely on technical help and early stage capital, typically provided by CDFIs, to make their dreams become reality. Innovation is required to drive demand and build new markets. The growth of the aquaculture industry is a prime example.

Chinese appetite for lobster and the Japanese demand for unagi (eel) help build markets for Maine’s fisheries products. A relationship with a sister state in Japan has led to importing technology to develop scallop farms in Casco Bay. Meanwhile, nutritious kelp smoothies and kelpcicles are examples of new products connecting consumers and out-of-state buyers with Maine enterprises. Expanding connections to US and global markets requires capital and capacity, as well as innovation in the supply chain, to ensure that Maine businesses meet new—and sometimes different—customer needs and expectations. Catering to foodies aligns with Maine’s history as a tourism and recreation destination.

6. Commitment to Place: Building a Rural Economy

Rural regions represent two-thirds of the US land mass, yet only 14 percent of the population, or 46 million people. Recent studies show that rural economies and demographics are highly diverse but experience an outmigration of young people seeking opportunities elsewhere, perpetuating an economic struggle.

Since 2000, Maine has lost a net of 37,000 middle-class jobs, mostly in manufacturing. Approximately 5,000 of these were due to paper mill closures and related forest industry businesses. They are being replaced in great part by lower-wage jobs in the retail, tourism, and service industries.

Some rural areas are successfully combating this trend by transitioning to a post-industrial economy with thriving small businesses and associated ecosystems. Others are leveraging abundant natural resources for their economic sustainability.

Maine, interestingly, is a mix of realities. Long the poorest and most rural state in New England, Maine ranked 33rd nationally in personal income per capita in 2016. Maine’s economy has lagged the nation in recovering from the Great Recession. The average wage in the state was 89 percent of the national average. Maine’s economic challenges are exacerbated by income disparity, with most of its economic growth taking place in the greater Portland region.

Community economic development demands a commitment to place, people, and sectors. Economic development in Maine requires traveling distances across geographies and cultures, sometimes by water. Persistence, flexibility, and tenacity are critical.

Listening to communities, identifying problems and vulnerabilities, and then advocating on behalf of industries and sectors are central elements of this approach. The larger success is measured by the sum of impacts, boat by boat, wharf by wharf.

About the Authors

Betsy Biemann serves as Chief Executive Officer of CEI. Previously, she led the Maine Food Cluster Project of the Mossavar-Rahmani Center for Business and Government at Harvard University. From 2005 to 2012 she was President of the Maine Technology Institute, investing in Maine companies and initiatives seeking to grow high-potential sectors of Maine’s economy. Prior to her move to Maine, Betsy served as Associate Director at The Rockefeller Foundation, where she managed a national grant and investment program aiming to increase employment in low-income communities. She joined Rockefeller’s staff in 1996 after working in international development.

Keith Bisson is President of CEI. Prior to assuming leadership of the organization, Keith managed CEI’s small business counseling, natural resources, and workforce development programs. He was also responsible for development and management of the $11 million Northern Heritage Development Fund; monitoring and participating in Federal rural development policy; and managing and developing foundation and investor relations.